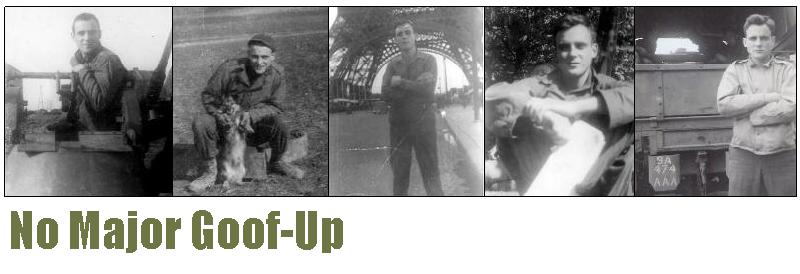

|

| Jack in his dress uniform |

The 474th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion, of which Jack became a part, began nameless as a group of recruits from up and down the eastern United States. There were men from large cities such as Baltimore, Washington, Brooklyn, Pittsburgh, Erie and Philadelphia, and others from small towns such as Bassett, VA, Tarboro, NC, and New Kensington, PA, where Jack hailed from. Little did they know as they boarded troop trains in December 1942 they would play a role in the greatest military event of all time: D-Day.

The trains themselves were described as “old, decrepit and depressing.”1 A 20-year-old Jack would add “dirty” to that list as he tells of his trip from home:

My instructions for entering the U.S. Army were to board the train in New Kensington with a large group of draftees and proceed to Camp Meade, MD. I think we arrived there sometime during the next day. We slept in our seats. The train was dirty, but, of course, we didn’t expect Pullman reservations. I wouldn’t call my stay at Meade an exciting one, but it was full of surprises, since none of the group had ever had this kind of exposure. Little did we know then that there were bigger surprises down the road. We received some shots and uniforms, took tests, pulled clean-up details to keep us busy and wondered what our destinations would be. I guess the chow was OK at this point, since I don’t remember anything too different from civilian life. Somewhere during this routine we were asked if we had any preference as to what type of outfit we would like to go to for our basic training. I never met anyone who ever ended up in the outfit he named!

|

| Lt. Steve Martinique of Coaldale, PA, was Jack's lieutenant. |

At this point, each man was also given a piece of brown paper, about a yard square, and a piece of string and told to use it to wrap their civilian clothes to be sent home. The Maverick Outfit shares an anecdote related to this activity that was indicative of life in the Army:

One man asked for another piece of paper for his hat. It was one of those broad-brimmed hats popular with the teen-agers in the early 40s. “Oh, that paper is big enough for the hat,” he was told, and the soldier supervising the recruits simply squashed the hat down with his hand.2

After about a week, Jack says the group was on a train headed toward New York City that ended up at Camp Edwards, CT. “This was a troop train with the usual accommodations,” Jack says, “which means we were glad to get the hell off of it when we arrived at our destination. I suppose they wanted us to appreciate our accommodations at Camp Edwards.”

|

| Sgt. Fletcher Marshall of Richmond, VA, was Jack's sergeant. |

The non-coms and officers, referred to as the cadre, were from New England and drawn from the 207th coast Artillery Regiment. It was formerly the 7th regiment of New York, an exclusive National Guard outfit made up of the area’s bluebloods, and was renamed the 207th when called into federal service.

“Basic training at Camp Edwards was very impressive for me,” Jack relates. “I really liked the marching, drilling, exercise, hiking, double-timing and instructions on small arms and the larger guns. But I didn’t care for the extreme cold weather or the ‘short arm’ inspections in the middle of the night.” As for the food, Jack says, “It wasn’t that great, although there was never enough of it to kill anyone. The post exchange was nearby and usually stocked well.”

He remembers one particular breakfast in the mess hall during a spell unusually cold for even New England when they were served cornflakes and water rather than milk. Their mess sergeant had overdrawn rations, so the cornflakes were limited to one bowl. Of course, the men could have all the water they wanted. Square eggs were served frequently as well, and Jack says these were OK “unless you bit into a lump of baking soda.”

Jack also remembers a humorous incident from a hike during this period. “My platoon leader asked me to identify a plane flying overhead at the time. I couldn’t identify it, and he said, ‘It’s an airplane, Clark.’”